Four years ago, I immigrated to the United States from France. To this day, I still can’t work, leave the country, have a debit card or get a driver’s license that lasts more than six months.

Four years ago, I immigrated to the United States from France. To this day, I still can’t work, leave the country, have a debit card or get a driver’s license that lasts more than six months.

I moved to Santa Barbara the summer before sophomore year of high school. My twin sister and I were excited to start school in a new country. We visited Santa Barbara a few days before the first day of school.

The day before school started, the lawyer in charge of my family’s case contacted my parents. She was direct, going to school could compromise my family’s chances of obtaining a five-year visa.

Yes, going to school. You heard that right.

Seriously, who makes those rules?

When my sister and I turned seventeen, our parents announced that we were applying for a green card. It should be a good thing for us, except it means not leaving the country for two years or we can’t come back.

It also means I might not be able to go to college after I graduate, and if I go to school I’ll have to leave the country from July 2019 until, well, who knows? Forget about four-year universities at this point.

I was miraculously allowed to continue my education on American soil, except for those few months. Luckily, money can buy anything. That is, if one can afford it.

After a few thousand dollars, hundreds of pages of paperwork, and an indefinite number of months, I will be the proud owner of an ironically titled advance parole paper that permits me to leave the country, although it “does not guarantee that you will be allowed to reenter the United States,” according to the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. As if it didn’t feel like incarceration already.

So now I’m a Dream Act applicant.

Dr. Reisz, Director of Institutional Assessment, Research, & Planning at City College, said only a mere 364 students filled out the Dream Act for the the 2018-2019 academic year, representing roughly two percent of students at City College.

As the Baby Boomers retire, immigrants and their children will take on the work by adding about 18 million people of working age between 2015 and 2035. According to The Pew Research Center, immigrants make up about five percent of the working force and are expected to drive future growth in the U.S. working-age population until at least 2035. It shouldn’t be so difficult for immigrants to obtain an American education considering how many of us are contributing to the workforce.

The purpose of this story is not for people to pity me. I am the best case scenario. I come from a wealthy European country that has a great relationship with the United States. What would my story be like if I came from Iran or the Philippines?

It wouldn’t take months, it would take years, maybe even decades.

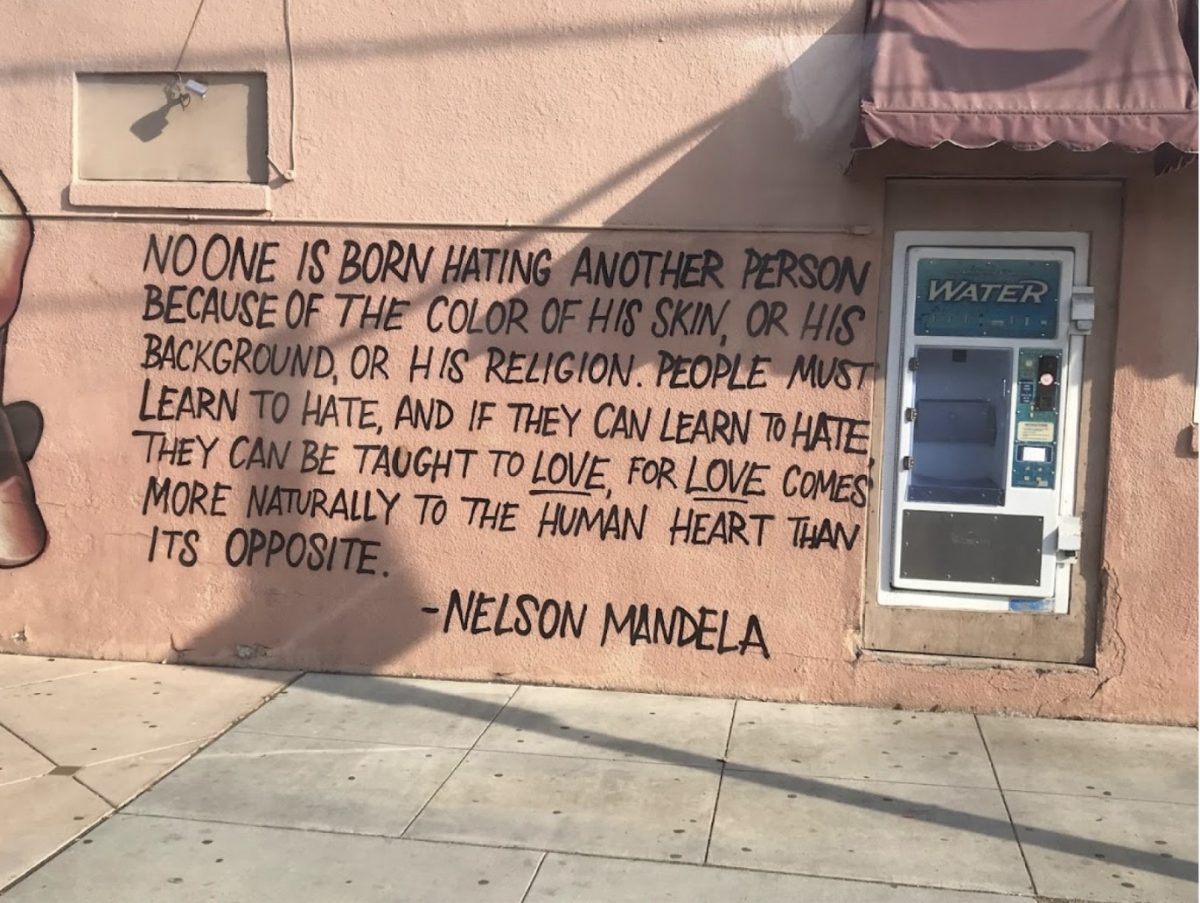

When it comes to education, immigration still has a lot to learn even in the safe haven that California seems to be. Vote for policies that make it easier, not harder. Advocate for ways to prevent students from having to put their education on hold for the sake of “being legal”.

Immigrants are just as important for America’s future as their education is.

You have the power, use it wisely.