Right off the coast of Santa Barbara is one of the world’s biggest natural oil seeps. Its natural abundance has benefited the community of Santa Barbara for decades.

In recent years, oil rigs were decommissioned in Santa Barbara due to the environmental effects, but the fleet of oil rigs right off the coast has become synonymous with the coastline.

There is a common misconception that the tar and oil that get stuck to the feet of beachgoers in Santa Barbara is due to the oil rigs. It is actually due to Santa Barbara’s natural abundance of oil.

The natural seepage has occurred in this region for thousands of years due to the Monterey Canyon, which is an underwater canyon right off the coast of California. The canyon is home to many deep-water sea life and a perfect place for sedimentary deposits.

One of the first people to utilize the seepage was the Chumash tribe. They would create handcrafted tools such as water bottles, fish hooks, and even bowls by incorporating tar and natural materials.

According to Brian Barbier, associate curator of anthropology at The Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History, the use of tar was observed only in indigenous tribes local to Santa Barbara. Tribes outside of the local region would use pine sap as a form of glue, which was harder to handle and less abundant.

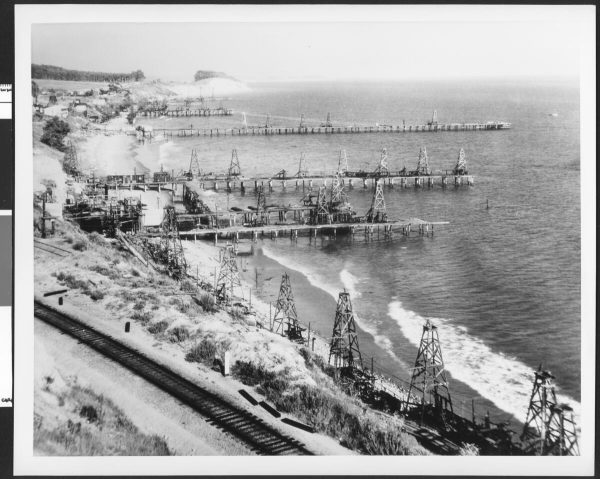

Santa Barbara’s abundance of natural oils allowed companies to start digging frequently around the region. Companies had been digging on land since the 1850s, until 1896, when the first offshore oil well was dug right off the beaches of Summerland.

“During the industrial revolution, petroleum products became more proficient in everyday life for humans,” said Director of Marine Diving Technology, Emma Horanic. “Obviously, it started inland with oil rigs that look like horses, until people realized, ‘hey there’s oil coming out of the ocean.’”

With Santa Barbara’s unique geological landscape, oil seeps that would usually occur further offshore happened to be reachable just by making piers off the beach. Consequently, this led to the world’s first offshore oil field, the Summerland Oil Field.

One of the major factors that inhibited the development of oil extraction was the inability to dive deeper than 150 ft. Going beyond this depth would induce nitrogen narcosis, which leads to decompression sickness known as ‘the bends.’

It wasn’t until deep sea diver Dan Wilson discovered heliox, helium-oxygen, in 1962 that oil companies were able to go into deeper water to dig wells, eventually establishing the fleet of oil rigs off the coast that we see today.

“Dan Wilson’s 400 ft. dive cemented Santa Barbara as the home of deep-water commercial diving,” Barthelmess said.

Wilson’s discovery became a catalyst for oil companies to go further offshore, closer to the source of oil, allowing the oil industry to pick up speed.

This rapid expansion of offshore drilling, driven by the pursuit of greater oil reserves, came with significant risks. The push for deeper offshore drilling, driven by obtaining a higher quantity over quality, sets the stage for disaster.

In 1969, an oil well pipe collapsed due to inadequate attention when drilling, which caused the biggest oil disaster at the time.

“When you drill for oil, you’re aiming for the fault line where the oil seeps out. You have to enforce the drill holes with pipes because of the immense pressure that builds up,” said Don Barthelmess, former director of City College’s marine diving technology department and current board member of the Santa Barbara Maritime Museum. “But Platform A had no reinforcements, which led to the disaster.”

The 1969 oil spill was the catalyst for the modern environmental movement. The National Environmental Act, The Marine Mammal Protection Act, and The California Environmental Quality Act

The Endangered Species Act and Earth Day were all founded because of a spill that occurred off the coast of Santa Barbara. Reminding the community of the deep-rooted connections Santa Barbara has with the natural oil.

“The famous pictures we see of birds and sea life covered in oil were from the 69′ disaster,” said Greg Gorga, executive director of the Santa Barbara Maritime Museum. “But it allowed for the people to push for protection of the environment.”

![Bingbong, a 1 and a half year old Belgian Malse Shepard mix, watches as a car passes by on Oct. 22 at the County of Santa Barbara Animal Shelter in Santa Barbara, Calif. "[Bingbong] is extremely playful, and enjoys his time with humans. He's a little stressed when he's left alone in the kennels...he really just wants a home," Animal Handler Dustin Fujuikawa said.](https://www.thechannels.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/AZFoster-3-1200x800.jpg)