From learning disabilities to life-threatening disorders, genetic counselors Jessica Kianmahd and Michelle Fox take complex data and explain it in a more understandable way, Wednesday it was time for students to take a look into this job.

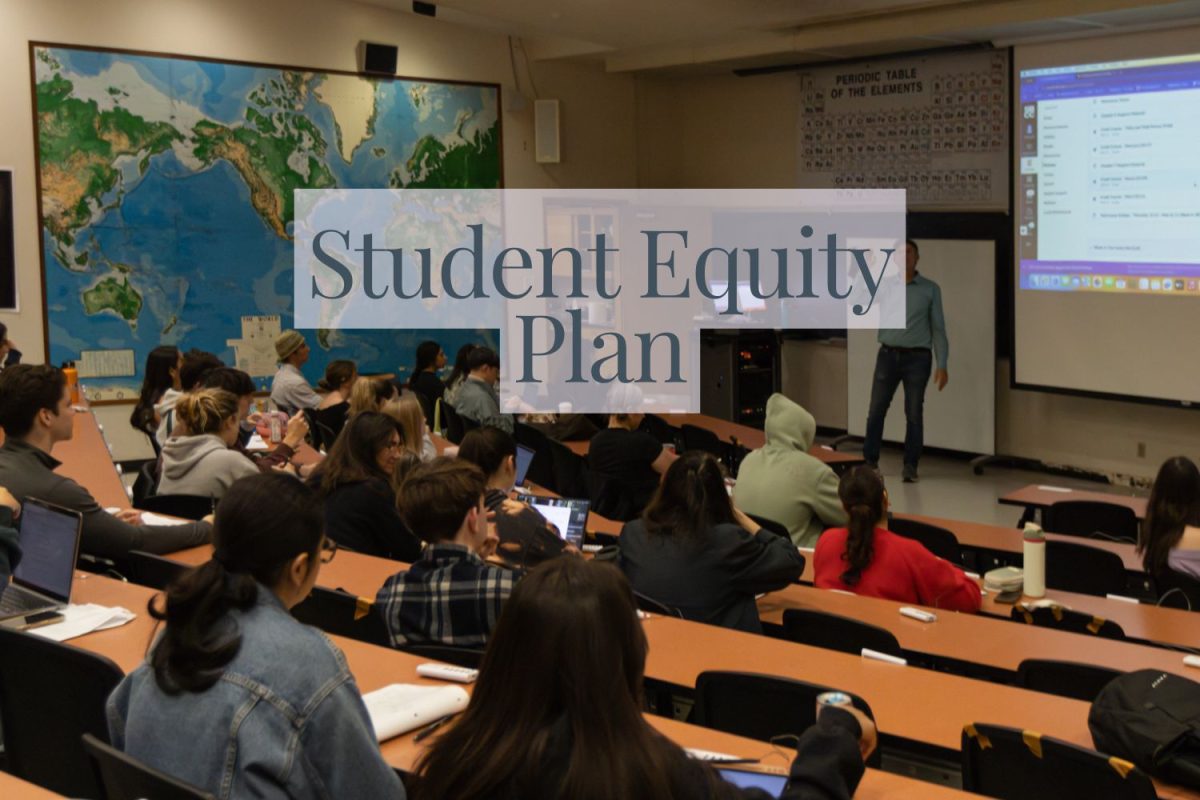

Hosted by City College’s Genetic Club, Kianmahd and Fox referenced a powerpoint elaborating on what a career in genetic counseling is like as students sat in the first few of rows in the lecture hall of Physical Science Room 101.

Fox recounted experiences with patients and expressed to the students how genetic counselors often form close relationships with their patients, more so than physicians.

“I’ve been doing this for 40 years and this is the best time of my life,” said Fox. “This is so much better than being a doctor.”

While describing some case examples, Fox talked about how all the skill sets of genetic counselors come into play. Emphasizing the importance of communication, she spoke about how depending on the specialty someone goes in to, they may end up having to deliver unexpected news.

According to the National Society of Genetic Counselors website, “Programs all require that you are trained in the three core genetics specialties: prenatal, pediatrics, and cancer.”

This enables future genetic counselors to branch off and focus on a specific area.

Counselors tend to work in “university medical centers, diagnostics labs, and private medical centers,” Kianmahd said.

The two-year master’s program prepares students for a job that combines science and communication skills. With ever-changing technology and a growing list of genetic disorders, there is “never a dull moment” in the career of a genetic counselor.

“I trained for a career but came out a better person,” Kianmahd admitted. “No two days are the same for me now.”

Kianmahd explained that those who go into the field have a 94 percent job satisfaction thanks to the broad spectrum training.

In the first row, student Jessica Kretschmer asked about the competitiveness of the less than 40 schools that offer genetic counseling graduate programs.

Kianmahd told Kretschmer that often times the programs can be competitive to get into and that it is important to “show programs and yourself that this is something you want to do.”

Kianmahd described the vetting process, explaining that schools want to understand an applicant’s thought process through a series of interviews and tests in order to determine if they are the right fit.

“My friend is president of the club and I wanted to know more information on the field,” Kretschmer said after the talk. “It definitely changed the trajectory of what I am doing.”

Club President Paige Awtrey said that she started the club because “community college is a good time to catch students [who want] a career in genetic counseling.”

Awtrey added that there is an increasing number of people who go into the field and “don’t want to work in a lab,” and that it is better to realize this sooner than later.

For students interested in pursuing a career as a genetic counselor, the National Society of Genetic Counselors website has pages dedicated to FAQs, lists of schools, and the role of a counselor.