In “Mourning/Warning”, Tia Blassingame provides a tactile look into her experience as an African-American woman and the shared experiences of black people in this country.

The exhibit, currently at the Atkinson Gallery and will be there through Oct. 12, invites its viewers to look into both the past and present experiences of African-Americans, utilizing touchable pieces of art and maritime symbols to its advantage.

Many of the pieces displayed are meant to be touched and interacted with, and Atkinson gallery director Sarah Cunningham said that this works to the advantage of the exhibit.

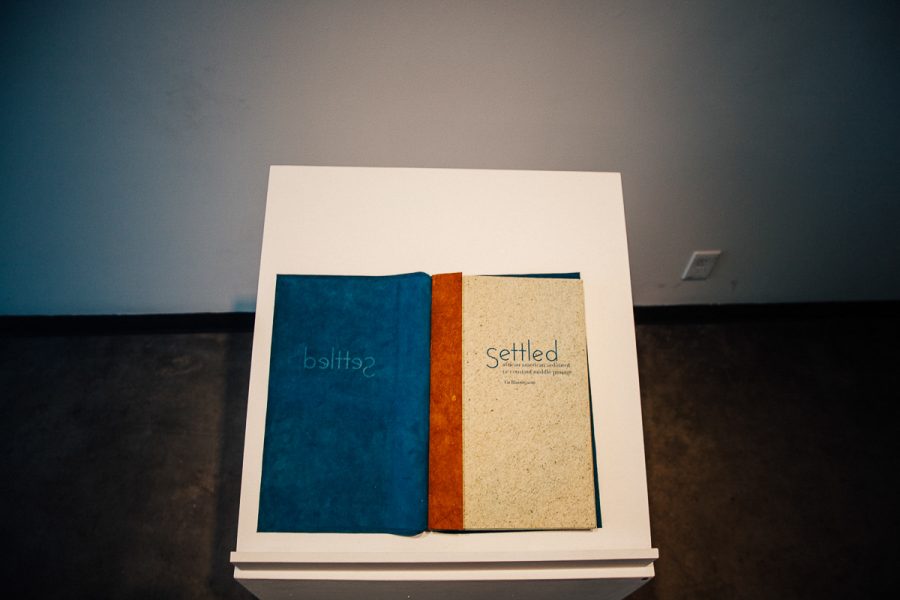

“It requires a presence,” she said, looking over one of the works displayed. It isn’t something that can be experienced by standing in the hallway. Many of the pieces are printed on paper, and bound together in a book that viewers will have to flip through in order to fully experience the piece.

“Frames on a wall is one experience,” Cunningham said about the books. “But still, the adjacency, touching them, one-at-a-time… I think that’s important.”

In her artist talk on September 27, Blassingame expressed the importance of the books. She said that when people step away from the books “[they] physically realize that [they’re] avoiding this subject matter.” The subject matter that she is speaking of is racism, and she believes that a conversation is essential.

“It’s not me and you having this conversation,” she said, “it’s you and the book.”

Blassingame often utilizes a process that was particularly popular in the 1960s and is known as concrete poetry. Concrete poetry gives a visual shape to the words in a poem, and she uses this, as well as the technique of letterpressing, to allow for both the “specific horror and the broader experience” that African-Americans face “to exist simultaneously,” Cunningham said.

Some of the African-Americans that are referred to by name include Eric Garner and Oscar Grant, both black men killed by police officers, who represent the aforementioned specific horror and connect to a broader experience and represent the nominal mourning.

The second half of the exhibit revolves around flags. These flags are reinvented maritime codes. Blassingame took existing warning codes and reinvented them, providing a warning to her fellow African-Americans. Cunningham explained that the United States history is connected to maritime history, which is in turn connected to slave history. Blassingame commissioned the same company that creates commercial warning flags to make those featured in the exhibit.

Some of the flags are strung outside, overlooking the Santa Barbara ocean, and Cunningham said that they have been confusing to some students who know maritime code. The students recognized the codes, but also were able to recognize that they were wrong, which they found to be disconcerting. Blassingame recognizes this, and considers it an alternate method of communication.

Not only that, but she recognizes that Santa Barbara is a beautiful place, and she is utilizing it to give something to those who died.

The flags have allowed her to “find a way to honor them, be in this beautiful space, in the light, blowing in the breeze,” even if their lives were cut short. They are mourning those lost to racism, and warning those currently suffering from it.