Fire-breathing dragons, gods, and ghosts aren’t the first things that come to mind when you think philosophy, and yet they play a major part in “The Party Line,” Dennis Gagnon’s new philosophically oriented science fiction novel.

“You’ve got to suspend belief to a certain extent,” Gagnon said about the book. “This is a science fiction, with an emphasis on the word ‘fiction.’”

Published in February, “The Party Line” is a story told by an older narrator reflecting back to a journey he went on as a 17-year-old, when he discovered a strange “aethereal realm” full of fantasy creatures and disembodied conversations. Though the book is full of fantasy elements, it deals with traditional philosophical problems of consciousness, free will and moral responsibility.

“It was a journey back to my journey,” Gagnon said, explaining that the book was based on ideas he started exploring as a teenager back in the early 1970s.

Gagnon, an adjunct City College professor, grew up in Ventura and went to Ventura Community College before transferring to UCSB, where he studied philosophy. He started teaching philosophy at City College in the mid 1980s, and after moving away, returned to Santa Barbara to teach in 2010.

Gagnon started writing “The Party Line” last June, beginning it as a short story that would counterbalance his more academic writing on consciousness, the self, and suffering. He said he then realized that his philosophical interests could be worked into a fast-moving narrative of science-fiction, in which one could do “lightning rounds of philosophy.”

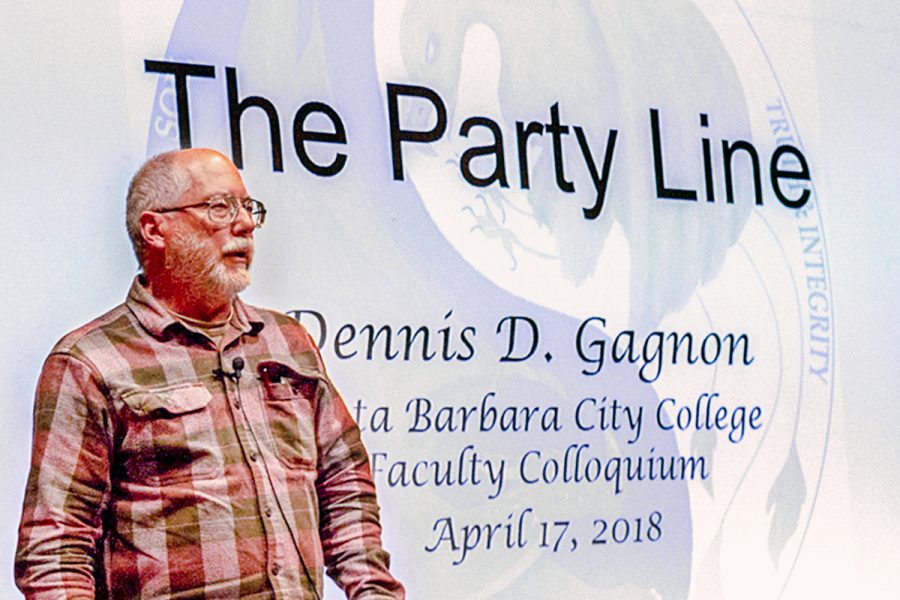

In a faculty colloquium last Tuesday, Gagnon discussed his book, sharing the stage with City College astronomy instructor Sean Kelly. Kelly contested some of the philosophical arguments in the book, but said he enjoyed reading it.

“For someone who’s not versed in philosophy, it gives them, in a singular book, a chance to explore a bunch of ideas,” Kelly said. “It will benefit them greatly just to hear them, in a way that’s not overly difficult.”

In his book, Gagnon writes a dedication to H.G Wells, Jules Verne and Edgar Allan Poe. He said that authors like Poe have paved the way for his own approach with the book.

“Edgar Allen Poe is so introspective that a lot of people find it hard to get into his work because it’s like delving into his mind,” Gagnon said. “It’s like one big mind trip, and my book is incredibly introspective.”

Gagnon’s book gets its title from an old type of telephone service, the party line, which allowed a group of people to share one phone number and communicate over it. The narrator in Gagnon’s book starts picking up on similar conversations other people are having through unconscious sensory communication, and finds that they take on a life of their own.

In the colloquium, Gagnon likened the idea of the living conversations to social media today.

“People can get into their own silos and start creating an echo chamber, and start reinforcing each other in good and bad ways,” he said.

Gagnon quoted one of Donald Trump’s tweets about climate change being a hoax, along with a 2016 poll revealing that almost half of Trump voters believed leaked emails from the Clinton campaign used code words to hide pedophilia and human trafficking.

“So how do we stop this madness?” Gagnon asked the audience. “We’ve got to realize that our thoughts and actions snowball into global concerns.”

Gagnon explained that the conversations in his book have a “bottom-up metaphysics,” meaning that the “monster” conversation fueled by meanness and hate is dependent on those below it.

“We all need to play our parts,” he said. “To kill the monster takes every one of us.”

“The Party Line” can be ordered online as an ebook or hardcover.