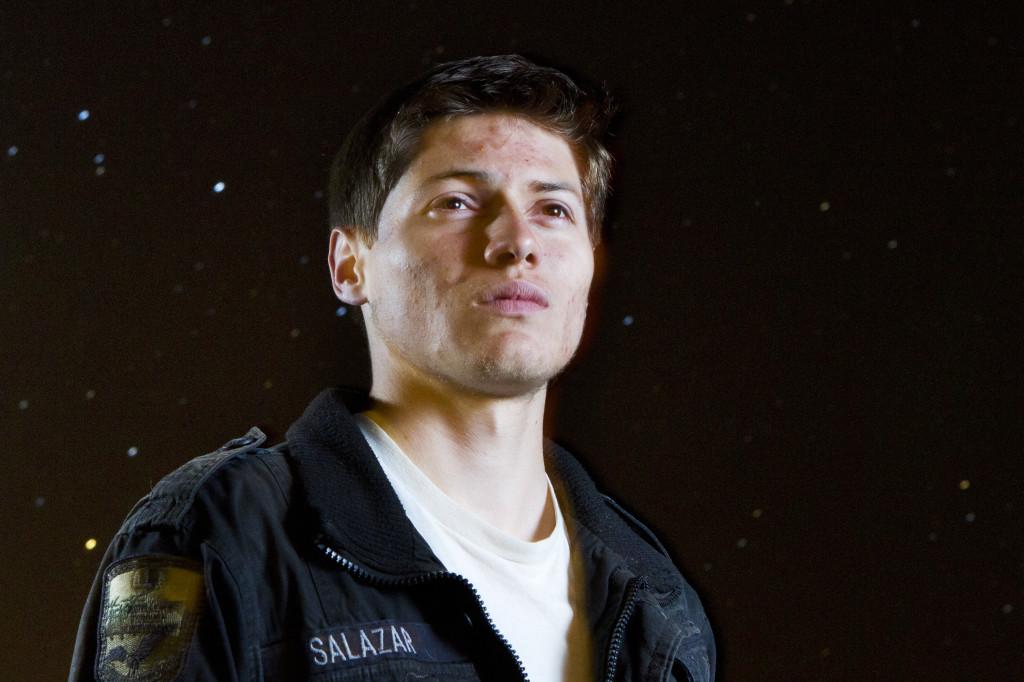

Robert Salazar found himself waking up in a blue Jeep Liberty, not knowing where he would find his next meal.

But that was three years ago.

“When something’s too big for people, they run away,” Salazar said. “When something’s too big for me, I accomplish it now so when something bigger comes up later, I’ll be able to handle it.”

That’s the kind of thinking that took a homeless teen out of his hopeless situation to his potentially revolutionary scientific discovery.

Salazar, 20, is a City College physics, geology, astronomy and mathematics major. His teachers say he is one of the most brilliant students with whom they have ever worked. A San Bernardino native, Salazar’s life didn’t truly turn around until his move to Santa Barbara.

His biggest success so far is his discovery of an effect in “nanostructured-thin metal film.” The effect literally turns the combination of light and metal into sound waves.

“We’re studying this in my group at UCSB because of Robert discovering it,” said physics Professor Dr. David Weld. “He’ll be an author if he publishes a paper on it.”

The discovery

On a warm night in July 2012, Salazar had been exploring the usefulness of nanostructured film for only four weeks.

He was cleaning up his desk in the physics lab at UCSB, where he works as an undergraduate researcher under Weld.

Salazar said he pulled out a flashlight from his pocket, and shined it on the almost perfectly black film.

It was just quiet enough in the lab that night for him to hear something unusual.

“I freaked out, my lab partner freaked out and when Dr. Weld came in and he didn’t know what it was, I was really freaked out,” he said.

“I thought, ‘If Dr. Weld doesn’t know what it is, it’s probably something really cool.’”

By accident, Salazar had just discovered a photoacoustic effect in the nanostructured film, a “singing metal,” all because his flashlight is able to flash 200 times a second.

”It’s so fast it heats up a thin layer of air in the microstructure..,” he explained. “It expands and makes a sound wave and when it cools down, it contracts and makes another sound wave.”

The first person to discover the photoacoustic effect was Alexander Graham Bell in 1880.

“But Robert discovered it in different materials and I think much louder,” Weld said.

Salazar is hoping to increase the flashing rate and produce sound at one million hertz, which means it could eventually be used in ultrasound machines.

“It can read ultrasound now, but not in the frequencies I need it to,” he said. “I still have to figure that out.”

All Salazar has to do now is finish his research, publish a paper and apply for a grant he most likely will get.

“It’ll probably be in the $10,000 range or so, somewhere around there,” he said. “Enough for us to keep doing research for a while.”

The young genius

He has an IQ comparable to naturalist Charles Darwin, but doesn’t believe intelligence can be measured in scales and numbers.

“He was three when he was drawing triangles and circles and squares,” said his grandmother, Yvonne Salazar, who still lives in San Bernardino.

“So I started teaching him words and letters, and he just picked it up, just like that, instantly. He was reading before he was in school.”

Salazar has studied geology, chemistry, biology, astronomy and paleontology to name a few, and is self-taught in some of them.

When he was born, his dad gave him an orange stegosaurus with blue back plates. At 4, he wanted to become a paleontologist, once he knew what the word meant.

Today, Geology Professor Jeff Meyer, teaching paleontology, said Salazar knows more about the subject than he does.

“He’s taken all of our classes and… there’s no more classes in this department for him to take,” Geology Professor Erin O’Connor added. “So if you’re trying to figure out if he’s for real, he is for real.”

Dark memories

Beginning spring semester 2010, Salazar pushed himself to take an unprecedented sum of 75 credits at Santa Barbara High School in order to graduate on time, including a Japanese class at City College.

Around the same time, he said his mother started to gradually disappear for days, weeks and months at a time.

By May that year, she and her financial support were gone completely, forcing him, his two sisters and stepfather to make it on their own.

“Oh god, these are dark memories,” he said.

His gaze averted as if he was trying hard to remember.

“There was a giant roll of carpet over here, because we were all rolling our stuff up,” he said as he demonstrated their living room with his hands. “And I would sleep here, in between the rolled-up carpet and the wall. That was my room.”

When they finally lost the house, Salazar and his stepfather lived in his blue Jeep Liberty for about a week, before he went back to San Bernardino to stay with his grandmother.

“My stepdad was really there when that whole thing went down. We fought till the end without her,” he said.

Despite his desperate situation and packed academic schedule, Salazar managed to pass all his classes.

“I had no idea how I was going to pull it off, but I was used to that kind of thing… So I thought I’d figure it out as it went along,” he said. “I did what was necessary and I got a pass in each one, except for my AP environmental science class. I got an A. I really liked that class.”

A few months later, he got a call from his mother who told him she had lost the home she was now living in. All his belongings were being auctioned off in the storage unit she had stopped paying for.

He raced over and was able to save the one item that meant the most to him – his California Cadet Corps uniform decorated with the state record of 53 ribbons, nine medals and two honor bars.

For him, this was the turning point.

He was offered a share in a room in Santa Barbara downtown and has stayed there ever since.

“That was the last episode of doom I ever had.” Salazar said. “Ever since then, things have been not just better, but extremely much better. There’s just been nothing to be holding back anymore.”

Science saved him

Salazar received 10 scholarships totaling $10,000 last year.

He also was invited to present his research on nanostructured-thin metal films at the Society for Advancement of Chicanos and Native Americans in Science conference in Seattle.

“I’m applying for a NASA internship right now. It would be fun, but research is better,” he said.

Salazar believes science, nature and art are all connected, or at least it used to be in Leonardo Da Vinci’s time. But during physics genius Isaac Newton‘s time, the three areas got disconnected, he said.

One of his many missions in life is to fix that and show people “the grand reunification of art and science.”

“I want people to be able to have the capacity to look at the world like the way the trees grow, the way the ants move across the table, which is the same way data gets sent across the internet,” Salazar said. “If people could see that science and art weren’t that different, maybe they’d be more interested in one when they aren’t in the other.”

His passion for art is clear, watching his own designs of origami. He started at age 8 and had folded his first thousand by 10. Two pieces are on display at the George Page Museum in Los Angeles, where he donated 300 hours of volunteer work from 2009 to ‘11.

Dr. Robert J. Lang, one of the world’s leading origami artists, recognized Salazar and said he designs “some fairly complex work and some of the subject choices are quite clever.”

But nothing enthuses Salazar more than exploring nature. On Thanksgiving, he went on a 22-mile hike from San Bernardino to Lake Arrowhead.

“Oh, San Bernardino Mountains, that’s my playground. I can get up to 5000 feet in…one hour, 45 minutes,” he said. “I want to make it all the way to Big Bear. When spring break comes, we’ll see if I make it that far.”

Salazar is not interested in money or recognition; he just wants to help people.

“If you love your job, you’re getting paid the triple,” he said. “You’re getting paid the dollar, you’re getting paid the experience and you’re getting paid to love what you do.”