The culture of grandiosity that we have grown so accustomed to has one glaring problem that seems to seep into every inch of how we understand our world’s history.

This is, put plainly, the theory of “great men.” The notion implies that behind every great historical movement is the tireless, unrelenting life’s work of one individual, blessed with a leader’s soul upon birth.

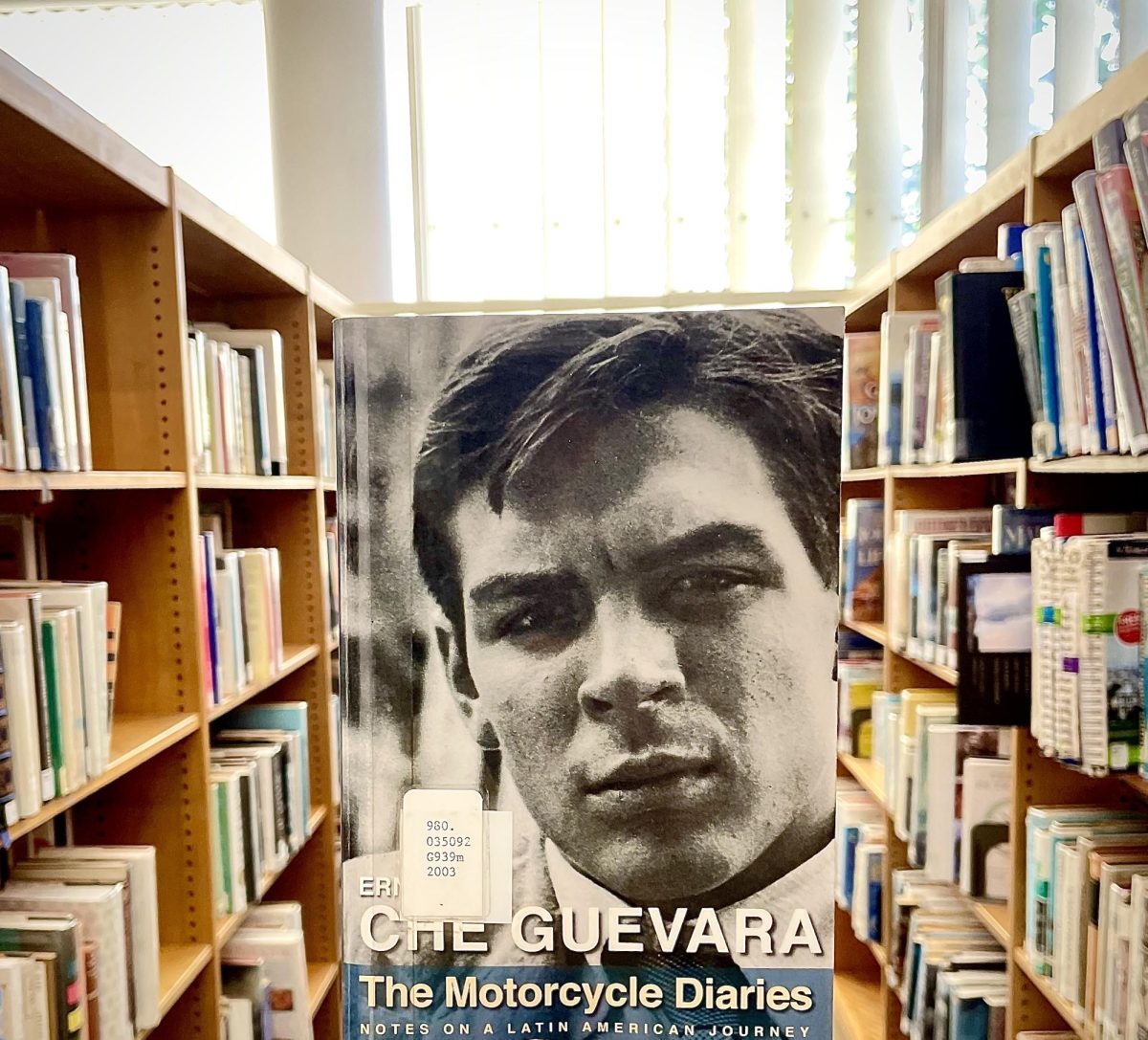

I first read “The Motorcycle Diaries,” by Ernesto “Che” Guevara because of my interest in the Cuban Revolution, and the political figures involved.

When I heard that one of the Cuban Revolution’s great leaders had gone from country to country, writing over a year’s worth of journal entries, I expected a deeply self-reflective book that preached some form of political theory– a biography of Che’s inner monologue on the capitalist framework that plagued the world.

And yet, as I plunged into the first few chapters, I realized that the book wouldn’t give me a single thing I expected.

The book follows a young Che, age 23, and his friend Alberto, 29. Both are medical students from relatively high-class families, who are planning a motorcycle trip together around Latin America.

What follows is a telling of pure human experiences, engrossed in new cultures, fueled by the passion of two rowdy young men who have never experienced this level of freedom.

I read as the two bummed their way through each sleeping arrangement, and I was surprised at the level of hospitality and charm of nearly every person the two characters came across.

At every crossroad throughout their journey, Guevara and Alberto were met with vibrant acceptance from the locals, with whom they would eat, drink and celebrate, usually ending with the two travelers sleeping on the floor of their kitchen, or in a work shed on piles of soft straw.

What I love about “The Motorcycle Diaries,” is that it isn’t a preachy preamble for Guevara’s role as a leader in the Cuban Revolution, nor his efforts afterward. The book truly feels like something a friend would write– overly descriptive of the beautiful lands they were traversing, and intricately describing the dynamic of people they came across with little judgment.

“It was close to nightfall when we left, but not before accepting the invitation to a typical Chilean meal,” Guevara wrote. “Tripe and another small dish, all very spicy, washed down with a delicious rough wine. As usual, Chilean hospitality wiped us out.”

Most of the book reads this way, recounting stories of human connection as they made their way through Latin America.

This book spoke to me because it led me to understand that every historical figure I put on a pedestal, thinking they were a born leader, was at one point just some kid, trying to figure out life and making friends with the people that shaped them along the way.

In the last few diary entries of the book, it is evident that Guevara’s mind is being swayed towards aiding a revolutionary cause; but his political intentions are never stated as divine truths, only observations of the world moving around him, and the people involved.

“I began to come into close contact with poverty, with hunger, with disease,” Guevara wrote about his experience with the working-class people he met on his journey. “And I began to see there was something that, at that time, seemed to me almost as important as being a famous researcher or making some substantial contribution to medical science, and this was helping those people.”

Overall, this book was inspiring to me because it gives you a taste of what leaders are like before they lead which is, of course, human. They eat, sleep, cry, laugh and dream just like anyone else, which is so much more evident after reading the journal entries from a man who at the time had no idea what his legacy would be.

Despite the cultural taboo that has been placed on Guevara’s name, I would recommend this book to anyone and everyone, no matter which way one swings politically. This story is one of adventure, survival and pure human connection, which transports you to what feels like an entirely different world; one that existed less than eighty years ago.